2005 Summer Reading

The Burial at Thebes

Death and Burial

by Prof. Mary Stange, Religion and Women's Studies

What makes us human? In trying to establish what essentially distinguishes homo sapiens from all the other animals, philosophers have compiled an impressive list of distinctly human qualities: We are the animal that thinks rationally, that manufactures and uses tools, that practices one or another form of religion, that creates art, that communicates symbolically, that makes culture, that laughs, that wages war. Yet, scratch the surface of any of these attributes, and it quickly becomes clear that they are neither truly universal, nor are they necessarily the sole province of human beings.

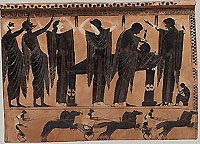

Archaic Greek black-figure plaque

depicting mourners tending the deceased,

ca. 520-510 BCE (Metropolitan

Museum of Art)

There is, however, one thing every human society, at least since the Neanderthals, has clearly had in common: an awareness of death as the inevitable endpoint of human existence, with a concomitant need to ritualize the passage from life to death, and to in one way or another “formalize the relationship between the living and the dead.”[1] Graves are among the earliest evidence of human culture.

For some peoples, ensuring a proper burial has protected the living against the malevolence of angry or restless ghosts. For others, it has been more a matter of seeing to it that the departed soul arrives in its afterlife safely, and often in appropriate style. Yet even where the conception of one or another form of continued existence does not play a conspicuous role, even when the dead person is a total stranger, the idea of the proper disposition of human remains nonetheless carries considerable force. Tsunami victims washed out to sea, murder victims who simply “go missing,” entire populations eradicated through genocide—take, for example, the Holocaust, Pol Pot’s reign of terror in Cambodia, mass killings in Rwanda and Darfur—these are ghosts that haunt our collective psyche. They strike a primal chord of horror at the defilement of individuals who are kin to us in nothing more, or less, than our shared humanity. Sophocles’ Antigone—with its precipitating action, The Burial at Thebes—sounds this chord as resonantly for us today as it did for the Greeks 2500 years ago.

Depictions of funerals are among the earliest surviving Attic art, dating back to roughly the 8th century BCE. Amphoras, kraters, and other objects created with the explicit purpose of honoring the departed illustrate various aspects of the ritual observances surrounding death and burial, particularly the laying out and transportation of the body, and the ways in which the survivors “salute” the dead. Two features of this archaeological record stand out as especially relevant to the Antigone. The first is that, as one author has phrased it, “What was celebrated was not so much the memory of the dead as the piety of the living.”[2] Thus, these commemorative objects uniformly depict the various aspects of mourning, and the ways in which the community of the living perform their prescribed ritual duties, as these are determined by their relationship to the deceased. Each death creates a breach in the social circle which needs to be closed. Family, friends, servants thus all had their well-defined parts to play in the process of restoring the community to equilibrium.

This relates to the second striking feature of Greek funerary objects: women played prominent roles the in funeral rites. Indeed, in Athenian society, where in so many other ways women were denied any meaningful social or religious functions, they were essential participants in the rites attending to death and burial. Women who were closest to the deceased were the ones who tended the body and prepared it for burial. Female relatives were the chief mourners, their ritual wailing (or “keening” in Heaney’s text) a crucial part of the wake. These female mourners were usually portrayed in a much more intimate relationship with the body than males who are generally shown at farther remove, and emotionally impassive. Women were also responsible for placing gifts in or on the tomb, in honor of the dead. And in the cases of slain warriors, women were commonly depicted as the ones who welcomed the hero’s body home for interment.

In this light, Antigone’s impassioned determination to give Polyneices’ corpse a proper burial clearly makes historical sense. As a woman, it is her responsibility to “throw him the common handful of clay” (p. 7), to pour “the water three times from her urn/Taking care to do the whole thing right” (p. 28). And as his sister, she has particular obligations to the fallen warrior, obligations dictated by kinship, as she reminds her reluctant older sibling Ismene, when she taunts her:

Are we sister, sister, brother?

Or traitor, coward, coward? (p. 8)

And later, when she declares to Creon:

Not for a husband, not even for a son

Would I have broken the law.

Another husband I could always find

And have other sons by him if one were lost.

But with my father gone, and my mother gone,

Where can I find another brother, ever? (p. 54)

Stronger yet than the pull of kinship, however, is Antigone’s conviction that she is bound by a law that transcends Creon’s recklessly punitive decree against Polyneices’ burial, the law that demands the dead not be dishonored. She tells Creon:

If I had to live and suffer in the knowledge

That Polyneices was lying above ground

Insulted and defiled, that would be worse

Than having to suffer any doom of yours. (p. 30)

Antigone has the gods on her side in this argument. The blind seer Tiresias implores Creon to recognize the religious consequences of his hard-hearted law:

That body lying out there decomposing

Is where the contagion starts. The dogs and birds

Are at it day and night, spreading reek and rot

On every altar stone and temple step, and the gods

Are revolted. That’s why we have this plague.

This vile pollution. (p. 58)

The imagery here, and the motive force behind Antigone’s action in The Burial at Thebes, are rooted in what may come as close as there is to a truly human universal: the intimation that it is the duty of the living to do right by the dead, whatever that means in cultural context, and that our failure to do so has profound social and psychological effects.

[1] Lynne Ann DeSpelder and Albert Lee Strickland, The Last Dance: Encountering Death

and Dying (Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company, 1987), 42.

[2] Francois Lissarrague, “Figures of Women,” in Pauline Schmitt Pantel, Editor, A

History of Women in the West, Vol. 1, From Ancient Goddesses to Christian Saints (Cambridge,

MA, and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1992), 164.