2005 Summer Reading

The Burial at Thebes

Theater - Aristotle and Tragedy

by Prof. Lary Optiz, Theater

Aristotle and theatre? Wasn’t Aristotle a philosopher? Didn’t he invent the scientific

method? Well, yes. Actually he was perhaps the world’s greatest know-it-all – at least

he thought so. In addition to his nearly 200 philosophical writings and scientific

treatises, he also wrote extensively on the art of theatre.

Aristotle was born in 384 BCE in Stagira in Macedonia (northern Greece at the time).

The son of a royal physician, Aristotle studied with Plato for 20 years at the famous

Academy in Athens. Some time after Plato died Aristotle served as tutor to Alexander

the Great. When he returned to Athens after a 13-year absence he created a new school

called the Lyceum. He died in 322 BCE.

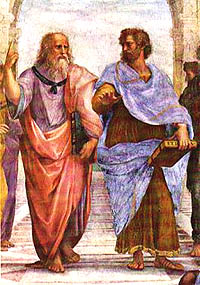

Pieter Paul Rubens, The School of Athens:

Plato and Aristotle (detail) 1510-1511

(Skidmore Visual Resources)

For the ancient Greeks the theatre was considered to be an important part of religious

observance. Further, they believed that tragedy was the highest form of drama. In

350 BCE, about 100 years after Sophocles wrote Antigone, Aristotle created an analytical

treatise on literature and drama entitled the Poetics. In this work he defines tragedy

and outlines what we now refer to as the elements of drama. The bulk of the Poetics

deals with tragedy and only mentions other forms, such as comedy, peripherally, perhaps

because the treatise is an incomplete collection of lecture notes. The Aristotelian

interpretation of drama has had a profound impact on our understanding of how tragedy

works, admittedly through the lens of one 4th century BCE Greek thinker. Aristotle's

vision of the dramatic arts does not necessarily encapsulate the meaning of tragedy

during its apex in 5th century BCE Athens, but its influence on western drama and

thought left an enduring impact which deserves consideration.

While Plato taught that tragedy is a danger to society because it encourages irrationality,

Aristotle argues that tragedy is both positive and useful since it not only arouses

pity and fear, but also purges these emotions, and thereby restores harmony to the

human soul.

The Nature of Tragedy

According to statements in Aristotle’s Poetics, tragedy is defined as:

“An imitation of action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude ... concerning the fall of a man whose character is good ... whose misfortune is brought about not by vice or depravity but by some error or frailty ... with incidents arousing pity and fear effecting the proper purgation of these emotions.”

A dictionary defines tragedy as “any serious and dignified drama that describes a

conflict between the hero (protagonist) and a superior force (destiny, chance, society,

god) and reaches a sorrowful conclusion that arouses pity or fear in the audience.”

A tragedy is a genre (distinctive type or form) of drama in which the role of humankind

in the universe is questioned in a profoundly serious manner. Tragedy assumes that

there is something wrong in the universe and a conflict between human goodness and

reality is implied. A protagonist (hero) generally suffers some sort of serious misfortune

that is not accidental, but is significant in that the misfortune is logically connected

to the actions and choices of the hero. Humans are seen as vulnerable beings whose

suffering is brought on by either or divine actions. A person may be destroyed by

attempting to be good or virtuous. This hardly seems fair, but it is often part of

the human experience. Why should someone suffer for trying to be good? Given this

idea of tragedy, if the gods reward goodness either on earth or in heaven there is

no tragedy. If in the end each person gets what he or she deserves, there is no tragedy.

Sometimes a main character might have a serious fault, or tragic flaw, which leads

to consequences far more dire than he or she deserves.

Tragedy generally has an unhappy ending. Often feelings of pity and fear for a hero

are aroused. Indeed, these feelings might be aroused for the human condition itself.

However, tragedy is not merely about feeling sad. As we watch the defeat of a virtuous

hero we encounter feelings of joy and glory because of humankind’s greatest aspirations,

qualities and potential. We admire the hero and, by analogy, we admire and celebrate

all humankind. We are hopeful because our belief in the human capacity to transcend

evil is reaffirmed.

Aristotle's Six Elements of Tragedy

- Plot

The plot is the telling of the story of the play – it is “what happens,” not what it means. Drama is the Greek word for “action.” The plot involves the action of the play and consists of a rhythmic pattern and flow of arranged events that follow one after the other according to a plan of cause and effect. The plot is the calculated progression of actions, events or incidents. Aristotle referred to the plot as the “soul” of drama.

Plot has to do with conflict and challenges. Obstacles are placed in the path of the characters preventing them from getting what they want. Often there are opposing characters (protagonist and antagonist) or forces in the play. The plot presents events in which these opposing forces clash until there is some form of final resolution (catastrophe).

Plot, therefore, is the dynamic presentation of characters placed in a dramatic situation in which they are compelled to act and react. It is the intellectually and aesthetically satisfying working out of events in a logical manner with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

The climactic plot is the most traditional form. It begins with the exposition of a problem, builds on a series of complications leading to a turning point, a major emotional climax and, finally, a resolution. - Character

The characters are the agents of the action. In Greek drama the characters are primarily the functionaries of the plot. A character does only that which is dictated by the necessities of the plot. It is only with Shakespeare that characters begin to be well-rounded personalities with lives of their own. - Language or Diction

This involves the spoken word; stylistic and formal choices for the dialogue and poetry of the play. There are conscious and varying arrangements of words, styles, images, etc. Although today we tend to rely more heavily on visual information, plays have always been written to be heard, not just seen. Since tragedy deals with heightened ideas and characters, it is not surprising that it often utilizes heightened language. - Thought

This refers to the thoughts of the characters and the underlying ideas and meanings imparted and explored by the author. The central theme of a play expresses some perceived universal truth about the human condition. Ideally, a play serves to both instruct and to entertain. Often the play’s theme is not readily apparent and emerges only after study and thought. - Music or Song

In ancient Greece the tragedies were always accompanied by music (often flute and drums). The chorus sang and danced their passages and the dialogue was chanted rather than spoken. Today we would include all sound effects and underscoring. - Spectacle

This involves all of the visual effects, including scenery, costumes, lighting, gesture, movement, spacing and other visual elements – everything that appeals to the eye. Aristotle considered this to be the least important element observing that it should contribute to the action and never exist as simply decoration or merely for its own sake. The word “theatre” is derived from the Greek word theatron which means “seeing place.”

Other concepts in Aristotle’s Poetics

- The protagonist must not be so virtuous that we are simply outraged instead of feeling pity or fear at his or her downfall. Nor should he or she be so evil that we seek his or her downfall in the name of justice. The true hero is one “who is neither outstanding in virtue and righteousness; nor is it through badness or villainy of his own that he falls into misfortune, but rather through some hamartia ("flaw").”

- According to Aristotle, the character should be highborn, famous or prosperous, like Oedipus or Antigone. A hamartia may be simply an error in judgment or may be a moral weakness, such as hubris ("excessive pride").

- Tragedies should not be episodic. Rather, the episodes in the plot should have a believable and inevitable cause and effect connection with each other. This connection is best when it is unexpected.

- Complex plots are better than simple plots and should have recognitions and reversals. A recognition is a change from ignorance to knowledge. This applies to any self-knowledge the hero gains and any insight to the human condition, provided that that knowledge is associated with the hero's peripeteia ("reversal of fortune"). A reversal is a change of a situation to its opposite.

- The protagonist becomes self-aware and accepts the inevitability of his or her fate, taking full responsibility for his or her actions.

- A tragedy should involve some form of suffering and should end unhappily.

- Any pity and fear evoked should come from the events and the action, not simply from the sight of something on stage.

- Catharsis ("purification" or "purgation") of the emotions of pity and fear is key to Aristotle’s definition of tragedy. Our feelings of pity and fear are purified so that we understand them better in real life and our pity and fear are purged so we can face life with greater control of these emotions

The Aristotelian Unities

Renaissance scholars interpreted Aristotle’s theories of drama as expressed in his Poetics. They referred to what we now call the Unities of Time, Place and Action.

- Time: the play involves action or events that could logically take place in one 24-hour period.

- Place: the play limits the action to one locale or setting. This refers only to the actual events the audience sees – dialogue can provide information on events that happened years earlier or in another city.

- Action: the play deals with a single, central storyline – the plot focuses on a single principle character.

The unities provide structure and can fulfill a number of functions:

- heighten the emotional intensity of the play by building suspense and intrigue

- provide focus on a central issue or theme

- emphasize the moral aspects by suggesting that our lives are as brief as a single day so one must consider the moral consequences at this moment.

Not all plays follow these restrictive unities. Indeed, the development of drama throughout

the ages has involved the exploration of alternate structures. In the 1920’s the German

playwright Bertolt Brecht developed an “Epic Theatre” which argued against Aristotelian

theatre that point by point. Many modern, avant-garde and post-modern plays have completely

and consciously abandoned the traditional Aristotelian unities.

For a complete text of the Poetics in English, with some commentary, click here.