Faculty Readers Respond

- Minita Sanghvi (Management and Business)

- Kim Frederick (Chemistry)

- Jennifer Delton (History)

- Caitlin Jorgensen (English)

- Yelena Biberman-Ocakli (Political Science)

- Hope Casto (Education Studies)

- Michael Ennis-McMillan (Anthropology)

- Sheldon Solomon (Psychology)

- Christine Reilly (Computer Science)

- Julie Douglas (Statistics)

Minita Sanghvi, Management and Business Department

As a qualitative researcher I look at the stories beyond the numbers. Therefore, I found this book to be an interesting read because Rosling tells us a story with numbers. Lots of numbers. Big data, as we call it now, especially in fields such as retailing and business. But Rosling is also cognizant of the way we look at data. Context is critical to understanding it.

Some of the data was heartening and his explanations as to why many think the world is still quite terrible made sense. Incremental positive developments hardly make news, but wars and disasters do. Globalization and technology have made our world smaller; our world is more transparent and news of adversity reaches us faster today. But because of this, help reaches disaster locations faster too.

One of the things I liked about this book was the diverse ways Rosling uses data to understand one problem. For example, when it comes to Climate Change and carbon emissions, in chapter five, he shares the story of how an environmental minister of an EU nation stated, “China already emits more CO2 than the USA, and India already emits more than Germany” (140). But then he turns that story upon his head when he shares how the Indian panel member argued that carbon emissions should be counted per capita, not per nation. Rosling had long been “appalled at the systematic blaming of climate change on China and India based on total emissions,” which he likens to “claiming that obesity [is] worse in China” because of “the total bodyweight of the Chinese population” (141). But Rosling is still not done. He then turns the data around one more time on p. 215, when he presents yet another way of looking at it. He analyzes carbon emissions by income and shows how the richest billion people, often in level 4 countries, burn half of the fossil fuel each year. It is those countries, not the level 2 and 3 countries, that are to blame for climate change. All these different ways of considering the climate change data, whether it is per nation, per capita, or by income level allows for a deeper, more nuanced analysis on the usage. This reiterates his point about how context is critical to looking at data.

From a Management and Business perspective, this book and Rosling’s website Gapminder is valuable to explain markets, economies, and populations to our students. But as a marketing professor, I am still interested in the stories behind the numbers. As Rosling explains, “the world cannot be understood without numbers, nor through numbers alone.”

Top of page

I am a Professor of Chemistry. The specific type of chemist I am (an analytical chemist), means that my job is to test samples for contaminants. So, for example, I look for contamination of drinking water from nearby hydrofracking wells. The work that my students and I do is meant to put science in the hands of everyone, so it matters that my professional, scientific concern with contamination coexists with my roles as a mom, a wife, and an active citizen in the world.

The authors of Factfulness talk about the fear instinct. Their basic idea is that fear motivates us to make poor decisions because we can’t appropriately judge risk. One of the categories of fear is fear of contamination--mostly contamination from things that are unseen, such as chemicals or radioactivity. One of the examples the authors give is the fear of radioactivity in the aftermath of the Fukushima nuclear power plant disaster, when people fled the area to avoid exposure to radioactivity. While not one single person has died from exposure to radiation as a result of Fukushima, 1,600 people died in accidents during the evacuation. Similarly, the authors detail fears of chemicals that cause people to avoid using insecticides and then become sick from insect-borne diseases.

I see a similar phenomenon among parents who avoid vaccinating their children, some of whom are friends of mine. Their fear of injecting unknown chemicals into their child causes them to leave their children open to potentially deadly diseases. The recent outbreaks of measles across the US are the result of these choices. But it is hard to completely blame these parents, who see the incidence of diseases such as measles to be of relatively low risk to their children weighed against the even smaller risk that their child will have a negative reaction to the vaccine. Yet the low risk of infection from measles is because of the net effect of vaccination known as “herd immunity,” which results when vaccination rates are high (around 90%). So by choosing not to vaccinate, these parents are actually increasing the likelihood that their child (and other members of their community) will get sick because they eliminate the benefit of herd immunity. Furthermore, they are increasing the risk to infants (who are too young to be vaccinated), older adults (with weaker immune systems) and immunocompromised individuals such as pregnant women and people with immune deficiency diseases. So the perceived risk that parents are considering is not the actual risk because of their false sense of security with respect to herd immunity.

I will leave you (and my non-vaccinating friends) with the following quote from page 116-117 of Factfulness: “[I]f you are skeptical about the measles vaccination, I ask you to do two things. First, make sure you know what it looks like when a child dies from measles. . . . Second, ask yourself ‘What kind of evidence would convince me to change my mind?’ If the answer is ‘no evidence could ever change my mind about vaccination,’ then you are putting yourself outside evidence-based rationality, outside the very critical thinking that first brought you to this point. In that case, to be consistent in your skepticism about science, next time you have an operation, please ask your surgeon not to bother washing her hands.’”

For me, I’ll take both the handwashing and the vaccinations, please.

Top of page

There is much in this book that could be infuriating to a reader. The authors’ tone is blustery, a little too pleased with itself. They credit trade and economic development (i.e. capitalism!) with making people’s lives better. They are hyper-zealous about facts, as if the data on which their “factfulness” is based is unproblematic and beyond doubt. There is an imperialist air about their celebration of progress in parts of the world that are still “behind” in terms of income, health, and education. They are critical of activists for exaggerating the problems they are trying to solve.

Even so, there is a message here for anyone who thinks we – humanity, the earth – are going to hell in a handbasket. It is that we are not. Things are better than they seem, and not only that, it is human beings who have made this progress happen – all of us, not just white Europeans, but also (and more so) every girl in a poor region of the world who has dragged herself to a school, every village official who has procured a water purifier for the community, every family in Tunisia who has patiently acquired bricks to build a house over the course of a decade, slowly but surely. And guess what? These efforts have paid off. But we – the people reading this book – retain the time-worn idea that so-called poor “undeveloped” areas still make up a substantial part of the non-western world. The data shows differently.

The authors say the book is about “factfulness” and data-based thinking, and it is, but it is also and more interestingly about progress.

One thing you will discover in your upcoming college careers is that the whole concept of “progress” has fallen out of favor among social scientists and academic types. We put it in quotes to signal that it can no longer be taken at face-value, but must be questioned, challenged even, because of its close ties to imperialism, racism, and inequality. Conservatives of course have always condemned “progress” because it has destroyed – and continues to destroy – religion, patriarchy and tradition, but these days even progressives, idealists, and liberals are critical of the assumptions and tolls of “progress.”

And this creates a dilemma, because students here at Skidmore (and elsewhere) actually do want to help make the world better, to eliminate inequality, discrimination, poverty, disease, and hunger, to stop climate change, to liberate human creativity. But their efforts are often undermined by a crippling pessimism. Not only do headlines remind them how bad things are, but their professors will dwell on how past (and current) efforts to improve the human condition have validated imperialism, racism, and now something called neoliberalism. But how does one fight injustice, war, and myriad intersecting oppressions without a fundamental belief that we – humanity – have before and can today make the world better? Whether “factfulness” can solve this dilemma is open to debate, which makes this a great summer reading selection.

Top of page

As I write this, I am at home in Saratoga Springs, but I am listening to Luminous Radio Tamil from Thiruvananthapuram, India. I’ve never been to Thiruvananthapuram, but I discovered the Radio Garden website through Skidmore ethnomusicologist Ruth Opara. Listening to this radio station makes the world seem a bit smaller, in a very good way. That’s important, because our perceptions about distance (particularly the metaphorical distance between values, beliefs, customs, and people) can discourage hopeful engagement with the world.

Like listening to Radio Garden, reading Factfulness makes the world feel smaller. I often feel overwhelmed by the weight of the world, and Factfulness is a helpful antidote. As the Roslings note in chapter two, a situation can be bad and yet improving, and that progress is worth celebrating. In fact, I would argue that celebrating progress can motivate growth: instead of drowning in despair, we can see how actions (big and small) make a difference.

However, in reading Factfulness, I often doubted the authors and hesitated over their conclusions. Part of this may be pessimism created by what the Roslings call “the gap instinct.” Because all difference can look the same, people can rely too much on the assumptions of “us” and “them,” failing to see common ground. To that end, I’m glad my assumptions were checked by the data in the book. But another set of hesitations come from my growing desire to see the world particularly and on its own terms. I want more first-person accounts of what people eat and drink, how they pray, and what they value. I expect to be surprised by difference. And while the Roslings paint a beautiful image of progress, progress looks quite a bit like Sweden. Is the global trajectory for every nation to become as much like Sweden as possible? (I notice their assumption, of course, because their goal isn’t “America,” which is the yardstick most familiar to me!) In other words, the Roslings and I can both be guided by a colonialist lens: social value is defined by Western ideals and progress by assimilation to Western norms. (I notice this, for example, in the Roslings’ dismissal of larger families, which for some people have value beyond just population replacement.) Hans Rosling checks that impulse at various moments, like when Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma reminds him that Africans want to be not just the grateful recipients of tourism money but also the global tourists themselves. Those are important moments in the book, because they offer a perspective that the Roslings could not have seen on their own.

I do feel more hopeful after reading Factfulness. It also serves to remind me that, to most effectively engage a complex world, we need both big-picture data and first-person accounts of what people want for themselves. This brings me back to Luminous Radio Tamil. I can’t understand Tamil, but listening to music from Thiruvananthapuram is at least a gesture towards making the world a little smaller.

Top of page

Yelena Biberman-Ocakli, Political Science

I use Hans Rosling’s Gapminder program to help students visualize quantitative data, such as life expectancy, number of cell phone subscribers, or carbon dioxide emissions in different countries. These data can help us to better understand and address big dilemmas in political science, such as those concerning development, democracy, and security (or lack thereof). For example, in Introduction to Comparative and International Politics, my students and I use Gapminder to study global population growth. Colorful circles, with each circle representing a country and each color standing in for a region, move across time (located on the x-axis), starting with the year 1800. The circles move up and down across the y-axis to demonstrate change in population size. One of them always stands out – China. Its population today is over 1.4 billion. In 1800, it was still the most populous state with 322 million. India is not far behind. In 1800, it was 169 million, but now is projected to surpass China in about a decade, with over 1.5 billion citizens.

Population size, as well as other social and economic indicators, are crucial tools for making sense of the world. As Rosling painstakingly demonstrates throughout Factfulness, our vision of what actually exists in the world is often blurry. Like fish who cannot tell they are in water, we find ourselves submerged in preconceived notions that have become invisible to the naked eye. Rosling shows that journalists, even experts, and we ourselves have normal human instincts (or biases) that distort our reality. The answer that Rosling provides for this conundrum is to step outside of our comfort zone—but this does not necessarily mean swallowing swords. It does mean doing the hard work of critical thinking: questioning everything, including one’s own opinions, and embracing messy complexity rather than jumping to easy conclusions. It also means taking the time to learn – really learn – from others across different fields of inquiry and with diverse life experiences.

In the classroom we study new and enduring ideas that have reached us through centuries (sometimes even millennia!) of human experience, as well as the debates these ideas have provoked. We also explore the contexts that may advance, distort, or obscure such ideas and debates. So, for example, when a pundit on television states with complete confidence something that we know is very much debated, we may recognize that what is being expressed is not a fact but one of numerous possible perspectives; this raises the question of whether the pundit’s goal is to manipulate rather than educate the viewer.

In addition to developing critical thinking skills and engaging with the knowledge that has accumulated over time, Rosling models the value of conducting fieldwork. It was through his experiences as a young doctor in Mozambique and studying an epidemic in Cuba that he reached some of his most profound realizations. Contexts that are very different from ours allow us to see new possibilities – truly different ways of thinking and doing things – by heightening our sensitivity to what is actually happening around us.

Top of page

In a time when facts have been left to interpretation and even willfully ignored in public discourse, Hans Rosling’s Factfulness provides a welcome framework for understanding our world. With Ola Rosling and Anna Rosling Rönnlund, Rosling offers ten conceptual tools to empower us to shift our worldview.

I am particularly moved by these authors’ reminder that we should neither hope nor fear without reason. Rosling states that he is not an optimist but rather a “possibilist” (p. 69), referring to this refusal to engage in either pessimism or optimism when the facts do not support those stances. From this perspective, we gain agency as humans who can work to improve structures that create obstacles for those who want nothing more than an opportunity to live their best lives.

As an educational researcher, I took particular note of the statistics about girls’ access to education across the world. Even as an educational scholar, I fell for the trap of assuming that girls’ years of schooling was lower than it in fact is. And again, the agency that Rosling provides his readers is exemplified in his suggestion to both celebrate the success that has been achieved for young women who do have access to more years of school, while simultaneously recognizing that more work must be done to create access for those girls who still are denied schooling. As Rosling states, things can be both bad and better than they once were.

My own worldview was pleasantly adjusted by Rosling’s explanation of the “Generalization Instinct” that tricks us into assuming characteristics are the same across groups of people. As part of this conceptual tool, readers are presented with the reminder that we must “assume people are not idiots” and to ask the question “In what ways is this a smart solution?” (p. 165). Rosling’s example of a smart solution was the investment in bricks to slowly build a second story on a home in Tunisia. I find this question immensely useful for teachers to use when considering parenting choices that are beyond our experience. As a teacher, especially of young children, we work in partnership with parents and affirm their expertise of their own children. When flummoxed by parents’ choices, asking oneself in what ways that choice is a smart solution is always a better place to start than to assume it stems from poor judgement.

The tools provided in Factfulness are an excellent starting point for students entering into a liberal arts education. The beauty of exploring a range of new disciplines is to expand our ways of understanding the world around us. New frameworks allows us to expand and shift our worldviews in order to appreciate the variety of experiences and choices that exist for people in contexts different than our own.

Top of page

Michael C. Ennis-McMillan, Anthropology

Disease and suffering are fundamental aspects of the human experience. Hans Rosling highlights this fact in Factfulness. Yet, as a physician and humanitarian, Rosling also offers hope for alleviating suffering by confronting head-on the tendency to think with one single perspective about issues like health care. He is, after all, a “possibilist”!

As a medical anthropologist, I like the idea of becoming a possibilist. Confronting erroneous assumptions about human health is a key aspect of medical anthropology, a social science that explores human illness and healing across social and cultural contexts. I examine, for instance, how people create ideas about alleviating unjust forms of suffering, such as the suffering associated with water scarcity in Mexico or the suffering refugees experience in France. When discussing my work, I commonly encounter the notion that a market-based approach to health care allows US residents to benefit from the world’s best health care system. What a truly horrible big idea.

In Factfulness, Rosling challenges this big idea by reviewing positive global trends in human health, including lower rates of child death, infectious diseases, and accidents. Few people, however, know these facts. Instead, untrue beliefs about health care hinder possibilities for considering alternative means to foster healthy, happy lives, particularly for children.

Using nifty bubble charts, Rosling compares the United States with all nations in terms of wealth and life expectancy. Readers can easily discover that the United States, the “sickest of the rich,” spends more on health care than any other country in the world. Yet, the US life expectancy lags behind other countries, including other capitalist countries. Even with advances in biomedical science, the persistent single “bizarre idea” of market-based health care leaves many preventable and treatable health issues unaddressed.

What harm comes from possessing a bizarre big idea? First, this view prevents US residents from seeing improvements elsewhere and learning about alternative health care systems. Cultural misconceptions about US health care also obscure the fact that meeting basic needs, such as providing piped water services, improves health outcomes. Mexico does not spend nearly as much on health care as the United States, but Mexico’s approach to developing water systems and providing basic health care services means the country does not lag as far behind the United States as many people might think. Lastly, Paul Farmer, a physician and medical anthropologist, says that assumptions about US health care also ignore more “persistent plagues” – social inequalities that prevent people from gaining access to basic health services. For example, even with advances in new medicines, social inequalities have created and will continue to create conditions leading to new drug resistant diseases. In other words, new biomedical technology combined with market-based social inequality creates new forms of suffering!

Despite this situation, I remain hopeful. Learning to challenge the single perspective tendency, with facts in hand, I am more curious to know how human health trends have improved and can continue to improve. I look forward to encountering new facts as a possibilist anthropologist.

Top of page

"If a way to the better there be, it exacts a close look at the worst…"

Thomas Hardy

Factfulness is a timely and important book.

In the current political environment of “alternative facts,” where “truth is not truth,” and people are generally ignorant of, and indifferent or actively hostile toward, facts, Rosling et al.’s emphasis on accurate facts—and explanation for why and how cognitive and emotional processes undermine our apprehension of facts—is commendable and compelling.

Please also, however, consider that:

Facts are necessary, but not sufficient: Do not confuse and conflate facts with truth: “The pathetic superstition prevails that by knowing more and more facts one arrives at knowledge of reality” (Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom, 1941).

Facts are essential in pursuit of truth, but must be augmented by theory, without which one cannot know which facts are important: “Even scholars of audacious spirit and fine instinct can be obstructed in the interpretation of facts by philosophical prejudices. The prejudice…consists in the faith that facts by themselves can and should yield scientific knowledge without free conceptual construction” (Albert Einstein, Autobiographical Notes 1949).

Belief in the inevitability of progress is a secular religion: Enlightenment thinkers were confident that knowledge and technology produced by the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions ensured inexorable progress.

Increased scientific knowledge and technological innovation has undoubtedly benefited a large proportion of humanity, and for many of us, things have never been better.

However, John Gray (Heresies: Against Progress and Other Illusions, 2004) argues that the belief that progress is inevitable is based on wishful thinking to ward off existential anxieties: “Late modern cultures are haunted by the dream that new technologies will conjure away the immemorial evils of human life. But no new technology can abolish scarcity, do away with the necessity of choice or alter the fact of human mortality.”

Things could be worse than you think: Because we are culturally conditioned to view progress as inevitable, we are also prone to underestimate how bad things are or might soon be.

“Factfulness,” our authors argue, entails “recognizing the assumption that a line will just continue straight, and remembering that such lines are rare in reality…remember that curves come in different shapes” (100).

Agreed.

In Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed (2005), Jared Diamond documents how major civilizations can collapse abruptly in the midst of seemingly auspicious conditions due to: resource depletion, climate change, conflicts with enemies, strained relations with allies, and failure to recognize and effectively respond to these conditions. Sound familiar?.

FACT: When Earth warmed 10 degrees (F) 252 million years ago, 96% of all ocean species and 75% of terrestrial species were obliterated; it took some 50 million years to recover a modicum of biodiversity.

We are in danger of encountering similar climactic conditions in the next century or two, simultaneously depleting resources, ramping up hostilities towards enemies, insulting and abandoning allies – while increasingly alienating ourselves from nature and plundering the planet in a drug, alcohol, shopping, television, Facebook, Twittering stupor.

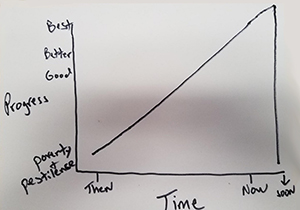

This would not bode well for humankind’s future prospects (see Figure 1).

(Figure 1)

Figure 1: How things could now be better than ever AND on the precipice of unmitigated disaster where we humans are directly responsible for our own extinction.

Top of page

Christine F. Reilly, Computer Science

As I was reading Factfulness, I reflected on how the various instincts presented in this book relate to my field of study, Computer Science, and specifically Database Systems. A recent achievement from this field is the distributed storage systems that enable the collection and use of huge amounts of data, commonly referred to as "big data in the cloud.” Data scientists employ machine learning algorithms—which are programs that use data to make predictions -to discover connections within the data. Many people currently interact with big data and machine learning through social media platforms (Facebook, Instagram, etc.). I have grown concerned about the amount of time that we spend using social media platforms, and the speed with which misinformation spreads through them. The Factfulness instincts I found to be most relevant to social media are negativity, fear, and blame.

Social media platforms utilize the negativity instinct and the fear instinct to keep consumers engaged, in the same way the news media does. Significantly, much of the content we view through social media is actually produced by the news media. Of course, a major difference between social media and news media is that social media platforms utilize the data they collect about consumers to provide customized content.

I could continue by stating that it is solely the responsibility of social media platforms to change these practices, which are often critiqued as an invasion of privacy and as the cause of a variety of problems in society. However, as discussed in the chapter about the blame instinct, the causes and the solutions are more complex. The demand for "free" use of social media platforms was initiated by consumers. This led the platforms to use advertising in order to run a profitable business; consumers now pay for these services with their personal data. This data is used as input to the machine learning algorithms that decide what content will be displayed to a consumer, with the goal of keeping the consumer engaged on the social media platform. A useful change the social media platforms could make is to provide easy-to-understand information about how they collect and use data, which would allow consumers to be more informed.

However, consumers can also change their behavior to decrease the negative impact of social media. A few months ago, I changed my habits and now rarely check social media and infrequently consume the news. My stress level has decreased, and I have more time to spend on hobbies and on meaningful engagements with my friends and family.

As you begin your college journey, I encourage you to reflect on your use of social media. Choose to have device-free meals where you have engaging conversations with your classmates. Choose to put your phone away when you go on expeditions around and beyond campus, and fully experience the world around you. During your time at Skidmore you have the opportunity to interact with people from a wide variety of backgrounds. I encourage you to put away your devices and engage with the community in a way that will expand your knowledge about the world.

Top of page

On March 2, 2017, more than one hundred Middlebury College students shut down a speech by controversial author and political scientist Charles Murray. A conservative student group called the American Enterprise Club (AEC) had invited Dr. Murray to speak. The AEC had also invited left-leaning Middlebury professor, Allison Stanger, to challenge Murray’s views and engage him in a public conversation after the talk. As a result of the student protest, however, Murray was forced to move to a private location and record his talk. When he was done and left the building, some of the protesters became violent, pushing and shoving Murray and injuring Professor Stanger, who was later treated for a neck injury and concussion.

What does this event have to do with Hans Rosling’s book about factfulness?

In 1994, Charles Murray and Richard Herrnstein published a book about intelligence called The Bell Curve. They argued, among other things, that differences in IQ are largely genetic, not environmental; that racial differences in IQ may be due to genetics; and that as a result, changes in the environment, for example, through educational interventions or other means, are unlikely to have much impact on IQ or racial differences in IQ. The Middlebury student protesters were objecting to Murray, in large part, because of these ideas, and whether they realized it or not, because of the simplistic notion that complex problems have single causes and single solutions.

In the twenty-five years since the publication of The Bell Curve, many new facts about intelligence have been discovered; nearly all of them undermine Murray’s claims. There was no evidence – then or now – that genetic differences underlie racial differences in IQ. Here are what we know to be some of the other relevant “facts” today.

Fact 1: Genes undeniably affect intelligence but strictly determine very little. For example, over 1,000 genes have been implicated in studies of intelligence. Yet any given gene has an extremely small effect, explaining less than 0.02% of the differences between people, and all 1,000 genes combined explain less than 20% of the variation in IQ among people.

Fact 2: The role of the environment is more important than initially thought. Perhaps the most striking illustration of this is that mean IQ scores have been steadily rising for the last 50 years. In other words, you are smarter than your parents, at least in ways measured by IQ tests.

Fact 3: The effects of genes depend on the environment. In a recent study, the heritability of IQ was about 70% in high-socioeconomic status (SES) families but only about 10% in low-SES families. This means that genes accounted for most of the variation in IQ in rich kids but little of the variation in poor kids.

What we are learning is that even defining intelligence is anything but simple. For example, when two dozen experts were asked to define intelligence, they gave two dozen different definitions. So beware of simple ideas and simple solutions, or as Professor Rosling warned, the single perspective instinct. Try to engage in constructive, respectful discourse with others, including people with whom you disagree. Had the Middlebury students allowed Murray to speak and had they engaged in a reasoned and informed discussion, we all might be better for it, including Murray.