units

conclusions

image banks

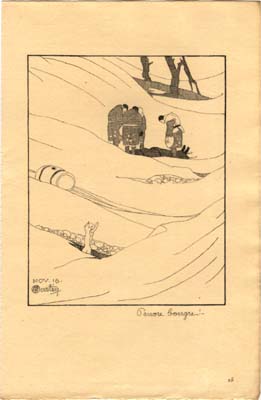

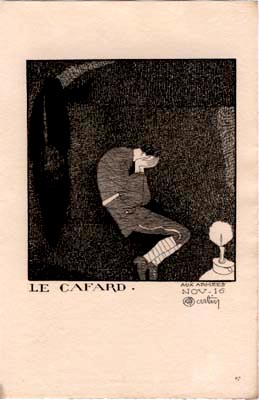

--l'assiette au beurre

--Les Quatre Saisons de la Kultur

|

|

From: A Very Long Engagement

The second man's number was 4077, issued at a different recruiting

office in the department of the Seine. He still wore the tag bearing this

number beneath his shirt, but everything else, all badges and insignia,

even the pockets of his jacket and overcoat, had been torn off, as they

had been from his companions' clothing. He had slipped while entering the

trenches and been soaked through, chilled to the bone, but perhaps this

was a blessing in disguise, for the cold had numbed the pain in his left

arm, pain that had kept him from sleeping for several days. The cold had

also dulled his mind, which had grown sluggish with fear; he could not

even imagine what their destination might be, and longed only for an end

to this bad dream.

Before the nightmare he'd been a corporal, because they'd needed

one and the fellows in his platoon had chosen him, but he hated military

ranks. He was certain that one day all men, including welders, would be

free and equal among themselves. He was a welder in Bagneux, near Paris,

with a wife, two daughters, and marvelous phrases in his head, phrases

learned by heart, that spoke of the workingman throughout the world, that

said . . . For more than thirty years he'd known perfectly well what they

said, and his father, who'd so often told him about the Paris Commune,

had known this, too.

It was in their blood. His father had had it from his father,

and had passed it on to his son, who had always known that the poor manufacture

the engines of their own destruction, but it's the rich who sell them.

He'd tried to talk about this in the billets, in the barns, in the village

cafés, when the proprietress lights the kerosene lamps and the policeman

pleads with you to go home, you're all good folks, so let's be reasonable

now, it's time to go home. He wasn't a good speaker, he didn't explain

things well. And they lived in such destitution, these poor people, and

the light in their eyes was so dimmed by alcohol, the boon companion of

poverty, that he'd felt even more helpless to reach them.

A few days before Christmas, as he was going up the line, he'd

heard a rumor about what some soldiers had done. So he'd loaded his gun

and shot himself in the left hand, quickly, without looking, without giving

himself time to think about it, simply to be with them. In that classroom

where they'd sentenced him, there had been twenty-eight men who'd all done

the same thing. He was glad, yes, glad and almost proud that there had

been twenty-eight of them. Even if he would never live to see it, since

the sun was setting for the last time, he knew that a day would come when

the French, the Germans, the Russiansó"and even the clergy"ówould refuse

to fight, ever again, for anything. Well, that's what he believed. He had

those very pale blue eyes flecked with tiny red dots that welders sometimes

have.

Sébastien Japrisot