units

image banks

--l'assiette au beurre

--Les Quatre Saisons de la Kultur

BASTILLE

(A)s the reality of the Bastille became more of an anachronism, its

demonology became more and more important in defining opposition to state

power. If the monarchy was to be depicted (not completely without justice)

as arbitrary, obsessed with secrecy and vested with capricious powers over

the life and death of its citizens, the Bastille was the perfect symbol

of those vices. (...)

And in some senses it was reinvented by a succession of writings of

prisoners who had indeed suffered within its walls but whose account of

the institution transcended anything they could have experienced. So vivid

and haunting were their accounts that they succeeded in creating a stark

opposition around which critics of the regime could rally. The Manichean

opposition between incarceration and liberty; secrecy and candor; torture

and humanity; depersonalization and individuality; open-air and shut-in

obscurity were all basic elements of the Romantic language in which the

anti-Bastille literature expressed itself. The critique was so powerful

that when the fortress was taken, the anticlimactic reality of liberating

a mere seven prisoners' (including two lunatics, four forgers and an aristocratic

delinquent who had been committed with de Sade) was not allowed to intrude

on mythic expectations. (...) revolutionary propaganda remade the Bastille's

history, in text, image and object, to conform more fully to the inspirational

myth.

The 1780s were the great age of prison literature. Hardly a year went

by without another contribution to the genre, usually bearing the title

The Bastille Revealed (La Bastille Dévoilée) or some variation.

It used the standard Gothic devices of provoking shudders of disgust and

fear together with pulse-accelerating moments of hope. In particular, as

Monique Cottret has pointed out, it drew on the fashionable terror

of being buried alive. This was such a preoccupation in the late eighteenth

century (and not only in France) that it was possible to join societies

that would guarantee to send a member to one's burial to listen for signs

and sounds of vitality and to insure against one of these living entombments.

In what was by far the greatest and deservedly the most popular of

all the anti-Bastille books, Linguet's Memoirs of the Bastille, the prison

was depicted as just such a living tomb. In some of its most powerful passages

Linguet represented captivity as a death, all the worse for the officially

extinguished person being fully conscious of his own obliteration.

IMAGES

(such ) images represented a systematic attempt by the propagandists

of Jacobin culture to build a new, purified public morality. The nation

would not be truly secure until those whom it comprised internalized the

values on which it had been reconstructed. Inheriting from Rousseau (albeit

in garbled form) the doctrine that government was a form of educational

trust, the guardians of the Revolution meant to use every means possible

to restore to a nation corrupted by the modern world the redemptive innocence

of the presocial child. On the ruins of monarchy, aristocracy and Roman

Catholicism would sprout a new natural religion: civic, domestic and patriotic.

(...) it was to images, in their broadest sense, that the Jacobin evangelicals

paid special attention. Fabre d'Eglantine (...) used sense-impression theory

from the Enlightenment to convince the Convention that "we conceive nothing

except by images: even the most abstract analysis or the most metaphysical

formulations can only take effect through images."

There was, then, an organized endeavor to replace the visual reference

points of the old France with a whole new world of morally cleansed images.

The public Salon of 1793, for example, featured, along with David's two

martyrologies, innumerable paintings in which domestic and patriotic virtues

were fused. The "Woman of the Vendée," for instance, in manyversions,

blows up herself and her family rather than surrender powder to the "brigands."

Child-heroes became important, among them the "young Darruder," who picked

up his fatherís weapon on the field of battle and charged the enemy with

it. At the level of popular art, tradesmen were encouraged to exhibit their

patriotism by displaying "civic boards" outside their shops in place of

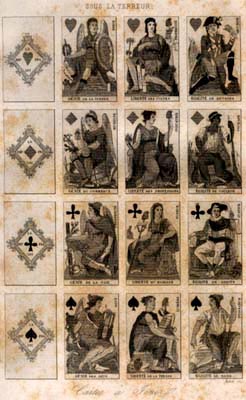

the traditional signs. Even playing cards were subjected to this épuration,

the queen of hearts being transformed into "Liberty of the Arts" while

the king was a sans-culotte general.

The most serious attempt to create a new "empire of images," in Fabre's

arrestingly modern term, was the invention of the revolutionary calendar.

This was also an attempt to reconstruct time through a republican cosmology.

The special commission appointed to make recommendations was a peculiar

mixture of literary men such as Fabre, Romme and Marie-Joseph Chénier

and serious scientists such as Monge and Fourcroy. Together the saw the

reform as an opportunity to detach republicans from the superstitions they

thought embodied in the Gregorian calendar. Their efforts were directed

especially at the rural world, to which the vast majority of Frenchmen

still belonged. In keeping with the cult of nature, the twelve months were

to be named not just after the changing weather (as experienced in northern

and central France) but in poetic evocations of the agricultural year.

The first month (which necessarily began with the founding of the Republic

in late September) was the time of the vendange, the wine harvest and thus

was called Vendémiaire.

REVOLUTIONARY VIOLENCE.

Popular revolutionary violence was not some sort of boiling subterranean

lava that finally forced its way onto the surface of French politics and

then proceeded to scald all those who stepped in its way. Perhaps it would

be better to think of the revolutionary elite as rash geologists, themselves

gouging open great holes in the crust of polite discourse and then feeding

the angry matter through the pipes of their rhetoric out into the open.

Volcanoes and steam holes do not seem inappropriate metaphors here, because

contemporaries were themselves constantly invoking them. Many of those

who were to sponsor or become caught up in violent change were fascinated

by seismic violence, by the great primordial eruptions which geologists

now said were not part of a single Creation, but which happened periodically

in geological time. These events were, to borrrow from Burke, both

sublime and terrible. And it was perhaps Romanticism, with its addiction

to the Absolute and the Ideal; its fondness for the vertiginous and macabre;

its concept of political energy as, above all, electrical; its obsession

with the heart; its preference far passion over reason, for virtue over

peace that supplied a crucial ingredient in the mentality of the revolutionary

elite: its association of liberty with wildness. (...)

There was another obsession which converged with this Romanticization

of violence: the neoclassical fixation with the patriotic death. The annals

of Rome (and occasionally the doomed battles of Athens and Sparta) were

the mirrors into which revolutionaries constantly gazed in search

of self-recognition. Their France would be Rome reborn, but purified by

the benison of the feeling heart. It thus followed, surely, that for such

a Nation to be born, many would necessarily die. And both the birth and

death would be simultaneously beautiful.