Sea life and our climate

Across the globe, tiny ocean organisms use huge quantities of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. When these algae and other plankton die, they often sink, locking their carbon in deep waters or seafloor sediments. By sequestering carbon, sea life helps slow atmospheric CO2 accumulation, a major driver of climate change. But the ocean’s carbon cycle is so complicated that biologists, geochemists, physicists, and other scientists need to study it in close collaboration—which is now a growing trend.

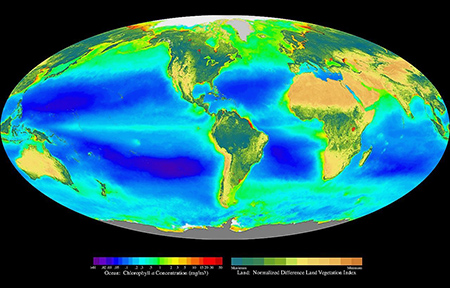

From satellite images, a NASA map shows plant-rich seas in bright green and blue.

Lower-plankton areas are dark blue, while algae overgrowths are red.

Meg Estapa, a member of Skidmore’s geosciences faculty, recently earned two federal grants, and a berth on a NASA cruise, for her research into cutting-edge sampling and analysis technologies for understanding how, when, where, and what kind of carbon-containing particles are descending from the ocean’s biologically richest regions toward the seafloor.

Over Earth’s history, oceans have absorbed far more atmospheric carbon dioxide (and emitted far more oxygen) than all the forests and fields on land. Hundreds of billions of tons of tiny algae (and lesser amounts of large marine plants) conducting photosynthesis make the planet’s atmosphere habitable—but their capacity to sequester carbon is limited and changeable. Estapa points out just a few variables: warmer water alters ecosystems, tiny particles sink more slowly than larger ones, algae eaten by animals get carried with their movements, particles often roil back up in currents and storms.

Scientists need to understand the complexities of the ocean carbon cycle if humans hope to predict, mitigate, and adapt to climate change. That’s why the National Science Foundation is helping Estapa and her students—and why she’s plying the Pacific with NASA scientists this winter. TV news interview with Estapa from the ship here; more video below.

Meg Estapa handles a floating trap for

collecting ocean particles as they sink.

With a $137,500 National Science Foundation grant and collaborators from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Estapa is comparing floating devices that collect drifting particulates and preserve them for chemical analysis, others that contain a gel to capture particles for microscope examination and size measurements, and even sensors that use a light beam to measure the quantities of carbon. These devices, roughly six feet long, are programmed to float at certain depths, collect samples and data for a certain time, and then rise to the surface for retrieval.

In a $77,000 NSF study, with scientists at the University of Rhode Island and San Jose State University’s Moss Landing Marine Lab, Estapa is comparing the chemical analyses of sinking plankton and other particulates with DNA sequencing. Beyond microscopic inspection, genetic analysis can fine-tune the identification of individual organisms. Skidmore’s research-grants coordinator Bill Tomlinson says Estapa’s securing of the award from NSF’s early-concept, exploratory program “speaks to the high value it places on this line of research.”

For Estapa, “The identification of the particles—algae, decayed matter, animal waste—by extracting their DNA will be an especially exciting aspect” of her work on this winter’s research cruise, which includes two colleagues from NASA and one from Sequoia Scientific. The team was granted the use of the R/V Falkor, a research vessel operated by the philanthropic Schmidt Ocean Institute, for a four-week study. NASA’s support reflects its interest in determining how in-sea data can best enhance the more general knowledge provided by ocean-color measurements taken from satellites.

Estapa says, “We’ll cruise from Hawaii to Portland, Ore., sampling a range of spots that we chose by studying satellite images. We’ll focus on some with relatively low levels of marine life, and we’ll also study richer areas as we cruise north into colder waters.” Using several techniques, she says, “our goal is to characterize the ecosystems that generated the particles before they began to sink into the depths we’re sampling.”