Financial aid, access, and the stress of success

by Peter MacDonald, with illustrations by Jon Reinfurt

Scope Magazine, Spring 2013

Two years after Mary Lou Bates graduated from college in 1972, she took a job at Skidmore’s

admissions office. Nearly 40 years later, and now the dean of admissions and financial

aid, she’s still making her daily commute, reading applications, visiting high schools

and college fairs, answering parents’ questions. And losing sleep over bringing in

each new class.

Two years after Mary Lou Bates graduated from college in 1972, she took a job at Skidmore’s

admissions office. Nearly 40 years later, and now the dean of admissions and financial

aid, she’s still making her daily commute, reading applications, visiting high schools

and college fairs, answering parents’ questions. And losing sleep over bringing in

each new class.

In other ways, the stresses and strains couldn’t be more different. In 1973 Skidmore received 1,700 applications, roughly 95% of which were accepted. In those "lean" years, Bates recalls, "a student with a solid record could show up in August and join the freshman class." This year, Skidmore received a record-breaking 8,200-plus applications, of which only 35% were accepted, a selectivity rate that underscores its standing as one of the nation’s top liberal arts colleges.

The angst for Bates and her admissions staff isn't about filling the class; it's about having to turn away well-qualified applicants when the pool of aid money runs dry. In 2012 the disparity between their financial need and Skidmore's available financial-aid dollars was $2.3 million. And that gulf is widening. Despite expanding its resources earmarked for financial aid year after year, ultimately the College must stay out of the red and refrain from drastic cuts in other areas. Says Beth Post-Lundquist, director of financial aid, "We’ve stretched as far as we can. We never want to turn anyone down because of money, but even with the infusion of new aid dollars, we simply don't have enough to go around, particularly when we need to honor the ongoing aid commitments to our returning students."

"It's incredibly hard any time

we can't admit a compelling

student because of limited aid

resources."

Of course, Skidmore has met the demonstrated financial need of thousands of worthy students over the years, and thereby helped transform their lives. Students such as Altagracia Montilla '12, a coach for a Chicago-based nonprofit that prepares underprivileged high school students for college. And entrepreneur C. Jerome Mopsik '06, a business analyst for a Saratoga-area company that acquires and manages animal hospitals. And Nancy Wells Hamilton '77, a partner with the Houston law firm of Jackson Walker who has a national practice in First Amendment law, intellectual property, and commercial litigation (with clients including Oprah Winfrey, CBS, and CNN). Their career successes—in many ways, the very shape and texture of their lives—are directly linked to the financial aid they received from Skidmore. An effervescent, first-generation college student from the Bronx, Montilla had no family resources to put on the table. Mopsik came from an upper-middle-class Philadelphia family, which translated into just a modest aid award; his parents gladly made the extra reach to send him and his sister to top liberal arts colleges. Hamilton, from Red Bank, N.J., would have been limited to a state school had it not been for Skidmore’s support, along with contributions from her grandparents.

"Financial aid did basically everything for me," says Montilla. Starting college was a huge step for her: "I was so lost when I first came to Skidmore. So alone. Now, I'm a completely different person—I want to say, woman—because I've grown up so much. I'm confident and happy. I don't feel like I'm behind anyone at all." As for getting virtually all of her college costs covered, the psychology major says, "I felt some initial guilt, because it was a lot of money and no one from home was doing what I was doing. Then I thought about all the work I'd put in to get to this point, and I realized that I deserved it. I was so motivated and wanted to prove myself—that was a big deal to me."

Beth Post-Lundquist digests a lot of

student-aid information so that

applicants don't have to.

(photo by Mark McCarty)

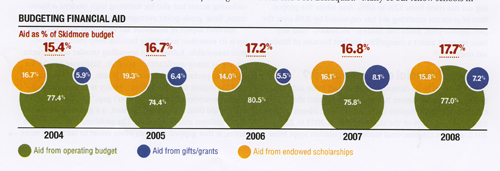

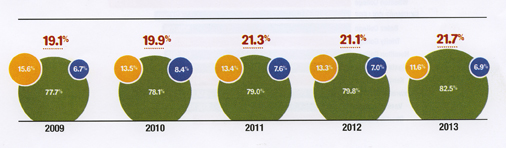

This year Skidmore awarded $36 million in grants to 1,150 students, about 44% of the student body. The average grant amount was $31,315—twice what it was in 2003–04. This 10% annual growth rate over the past decade has easily outpaced increases in Skidmore's comprehensive fee and overall US inflation. But it has also placed increasing stress on College finances, especially as employee health care, technology, and other costs have been claiming more budget dollars at the same time. As a percentage of its operating budget ($135 million this year), Skidmore aid has grown in the past decade from 15% to 22%, a clear reflection of the institution’s unflagging commitment to broad access. Alumni, parents, and friends have supported this commitment by contributing more than $60 million for scholarships over the same decade. Yet even with these investments, Skidmore officials have struggled to keep up with the demand. Between 2007 and 2013, the percentage of applicants requesting aid has risen from 52% to 68%. And while the proportion of students receiving aid has expanded by 20% over the past decade-plus, Bates still finds it "incredibly hard any time we can’t admit a compelling student because of limited aid resources."

What is financial aid really worth?

Thanks in part to its determination to find more aid dollars in tough times, Skidmore has seen an important shift in the composition of its student body. American students of color increased from 13% of the student body in 2003 to 22% in 2012, and the international student population leapt from 1% to 6% (today's students come from 43 states and 51 countries). These changing demographics are already being cited for helping to enhance the intercultural understanding of all students—a key goal of Skidmore's current strategic plan. "Recent studies and firsthand experience tell us that diversity increases the intellectual and cultural vitality of our academic community," asserts President Philip Glotzbach. "Likewise, it links directly with creative thought. Interactions among disparate perspectives frequently strike the intellectual sparks that herald the emergence of a new idea."

Bates is hardly one for hyperbole, but even she can't resist touting Skidmore's progress in opening its doors wider than they've ever been. She says, "Considering our relatively small endowment when compared with our peers, our commitment to access and diversity is second to none." Skidmore’s endowment is squarely in the middle in a 17-member peer set (with the likes of Vassar, Colgate, Kenyon, Sarah Lawrence, and Trinity), yet in student diversity it scored fourth in US News & World Report's 2011–12 "Campus Ethnic Diversity" breakdowns.

At the same time, Skidmore's retention rate (freshmen returning as sophomores) has been climbing and now stands at 92%, and its six-year graduation rate is 88%, both strong figures. One example Bates points to is the College's opportunity programs, which enroll and mentor students who come from disadvantaged secondary-school backgrounds but who show the ability and drive to flourish at Skidmore. Serving 170 students (over 5% of the student body), these programs have been hailed as national models not only for widening access but also for fostering high student achievement, from grade-point averages to graduation rates.

Another aspect of Skidmore aid that gives students a leg up is its attention to helping families keep their indebtedness reasonable. Rather than spreading smaller aid amounts among as many applicants as possible, Skidmore provides a complete package to each student it aids. As aid director Post-Lundquist says, "Skidmore’s policy is to meet the full need of everyone it admits; we don’t gap." Gapping, or offering less aid than a student's full need, is a growing practice at many colleges and universities. The problem, Post-Lundquist notes, is that gapped students often resort to taking on more loans, which at best makes for heavy debt burdens by the time they graduate; at worst, she says, "it adds the risk of extending the number of years it takes them to graduate, or even prevents some from graduating." Compared to its peers, Skidmore is in the lower third when it comes to the average debt of graduates. For the class of 2011 it was $21,000, well below New York State and national averages.

Mary Lou Bates and her admissions staff

really do love opening doors. (Photo by

Glenn Davenport)

Tuition economics

That Skidmore has boosted its financial aid budget and its diversity while maintaining its median SAT scores and even improving other academic measures is remarkable, given 2008's global financial crash and sluggish economy ever since. In the decade of 2001–11 American incomes from all strata, even the top 5%, did not rise, according to a College Board report co-authored by Sandy Baum, professor emerita of economics. With incomes still shrinking, the average student's net price (that’s out-of-pocket, work-study, and loan commitments, apart from grant aid) at a four-year school is up 4% from last year—double the rate of inflation. The average debt for a private-college graduate, $29,900 in 2011, also rose more than inflation, at 3.5%. Meanwhile, inflation-adjusted government funding for postsecondary education fell again, by 5%.

But in her analyses Baum also emphasizes longer-term trends, which are still positive for students hoping to attend private colleges. There, tuition and fees (adjusted for inflation) over the past decade rose just 2.4%, compared to 3% and 4.6% in the two previous decades. By contrast, those same costs for public colleges and universities grew twice as fast in the past decade, at 5.2%. Which is not to say there aren't warning signs for privates. Baum's concern is that "even the incomes of people at the top are going down, and those are the people who are supposed to be able to pay without dipping into their savings."

"Parents tell us about other

colleges' offers, and expect some

'merit' aid from us to sweeten

the pot."

At Skidmore 56% of families do pay on their own. An often-forgotten fact, however, is that the true cost of educating each Skidmore student is higher than tuition and fees. In 2011–12 the cost was pegged at $62,700, a full $9,000 more than that year’s $53,700 comprehensive fee. In effect, every student is subsidized to some extent by Skidmore's endowment earnings, donations, and other income. Still, the post-2008 economy has changed both the wallets and the mindsets of full-pay families, according to Bates and Post-Lundquist. "Many of our fellow schools in the top 50 of US News & World Report's rankings are providing non-need-based or 'merit' aid," Post-Lundquist says. "At some of our peers 30% of financial aid is non-need-based, while at Skidmore just 1% of our aid is." In today's admissions and aid race, she reports, "Parents tell us about the packages that other colleges are offering them and ask us what we can do. Or they tell us their child was admitted to a very selective elite school, so they expect some 'merit' aid from us to sweeten the pot."

With its emphasis on access and affordability, Skidmore has stood firm on restricting its non-need aid to the longstanding Filene Music and Porter Presidential Math and Science scholarships for about 12 incoming students each year. In reconfirming this policy at last October's trustee meeting, Skidmore leaders agreed to accept the price: losing some top applicants who get wooed elsewhere with 'merit aid' offers. "The bigger price," says Glotzbach, "would be turning our back on the principle that a Skidmore education should be available to qualified students regardless of their ability to pay. Arguably, every non-need-based dollar we offer takes away from what we can provide to those who truly need it. If we expect to graduate students who are ethical and who value the common good, then Skidmore has to model this kind of behavior."

These days, even the most elite and highly resourced schools are feeling squeezed,

according to a recent New York Times article on aid and diversity. Wesleyan had been "need-blind—admitting students without

regard to their ability to pay, because it knew it could meet their need—but it has

backed off slightly, now accepting 10% of its freshman classes from candidates who

can pay full fare. Another well-funded college, Grinnell, is also considering becoming

"need-sensitive." Williams and Dartmouth, which had provided their aid exclusively

through grants, are beginning to include student loans as part of their packages.

These days, even the most elite and highly resourced schools are feeling squeezed,

according to a recent New York Times article on aid and diversity. Wesleyan had been "need-blind—admitting students without

regard to their ability to pay, because it knew it could meet their need—but it has

backed off slightly, now accepting 10% of its freshman classes from candidates who

can pay full fare. Another well-funded college, Grinnell, is also considering becoming

"need-sensitive." Williams and Dartmouth, which had provided their aid exclusively

through grants, are beginning to include student loans as part of their packages.

There’s no escaping the math. "Skidmore’s current operating budget is predicated on 42% of our students receiving aid," Bates notes, "yet 68% of our applicants requested it." Earnings from the endowment provided nearly 20% of the financial aid budget in 2003–04, but after the down markets in recent years, that figure has fallen below 12%. Little wonder that Skidmore too is becoming more need-sensitive; Bates now estimates that the College accepts 25% of each incoming class with some consideration for the families' ability to pay on their own. "We’ve wanted to build our applicant pool in part to build the number and strength of those who don't need aid," she acknowledges, so this year's big spike in applications was gratifying on several levels.

Calculating needs and awards

Like almost all colleges, Skidmore builds

each aid package starting with a federal,

low-interest Stafford or Perkins loan,

usually restricted to $3,000 or $4,000;

next it adds a federally subsidized work-

study job, usually limited to about $2,000;

it looks for small state or federal grants to

add; and then it tries to fill the rest of the

need with grants from its own aid budget.

Last year Skidmore’s contributions ranged

from $2,000 to $56,000 depending on

demonstrated need.

One example: Felipe had $5,000 in savings;

his parents had $280,000 in home equity,

$30,000 in savings, and an annual income of

$105,000. Skidmore asked his parents to

contribute $8,700 of their income, $3,000

from savings, and $10,000 from a Parents

Loan and asked Felipe for $2,000 of summer-

job earnings and $1,000 from his savings.

Skidmore offered the rest, their calculated

need of $31,700, as a $26,200 College

grant, a federal work-study job for $2,000,

and $3,500 in federal loans.

A second scenario: Lisa lived with her

divorced mother, who had $60,000 in equity

and an income of $62,000 with child

support. Skidmore asked her mom to pay

$5,000 and her dad to pay $6,000 (in 10

installments over the year), while Lisa

contributed summer-job earnings of $2,000.

That left $43,400 in need, which was covered

by $37,900 in Skidmore grants, a $2,000

work-study job, and $3,500 in federal loans.

Price vs. value

Jerome Mopsik came to Skidmore as a transfer student, able to make the move thanks to an aid package that included one of the College's Palamountain Scholarships. Mopsik's father, Eugene, a Penn grad and executive director of a photographers' trade association, was unswayed by money matters. He avows "a deep personal commitment to higher education. It's the best investment parents can make to allow their children to take maximum advantage of what life has to offer." He says, "Skidmore’s value proposition was extraordinary: the resources per student were very inviting, the facilities were overwhelmingly good, the town had a lot to offer. Our family made a decision that we were going to do whatever we needed to."

Not everyone is as bullish as the Mopsiks about the value of a four-year degree. A recent New York Times article, "The Old College Try? No Way," asks pointed questions: Why go into debt with no guarantee of a job? Why not undertake your own self-directed learning, as UnCollege.org recommends? Why not just drop out like Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, and Mark Zuckerberg, who made millions? The answer, it turns out, is clear and compelling. Apart from very rare exceptions, it pays to go to college. A 2010 College Board analysis calculates that the median earnings of bachelor's degree recipients working full-time in 2008 were more than twice those of high school graduates. By age 33, these higher earnings offset not only the four college years spent outside the labor force but also the average tuition and fee payments at a public four-year university funded fully by student loans.

Moreover, grads from liberal arts colleges say they feel better prepared for life's challenges, including careers, than do those from private or public universities, according to a 2011 national study commissioned by the Annapolis Group, a consortium of leading liberal arts colleges. In the survey, 79% of liberal arts grads rated their college experience as highly effective in preparing them for a first job or admission to grad school, compared to 73% from private universities and 64% from national flagship universities. More striking was that 77% rated their undergraduate experience as "excellent," as against 59% from privates and 53% from flagships. On virtually every measure known to contribute to positive outcomes—challenging professors, small classes, mentoring—the liberal arts graduates rated their experiences more highly than did university graduates.

Additionally, liberal arts schools, while representing just 3% of American higher education, produce a disproportionate number of successful graduates and leaders. A 2012 count showed that, per capita, liberal arts colleges turned out twice as many students who earned PhDs in science as did other institutions. A 1998 study found that liberal arts schools turned out 19% of US presidents; 8% of the wealthiest CEOs and 8% of Peace Corps volunteers; 23%, 19%, and 18% of Pulitzer Prize winners in drama, history, and poetry; and many more.

The way forward

At the end of the day, financial aid isn't about numbers. It's about the students who are transformed by a Skidmore education because of that aid. And therefore it's also about the alumni, parents, and others who understand the value, not just to the student recipients but to the campus community as a whole, and who make that knowledge material as donors.

aid and have been forever grateful

to those who made that possible."

Lawyer Nancy Hamilton says, "I came to Skidmore on financial aid back in the 1970s and have been forever grateful to those who made that possible." She calls the growth in financial aid and diversity at her alma mater "a signature achievement" demonstrating that "Skidmore has its priorities straight." A trustee, alumni board member, and longtime supporter of scholarship aid, she has enjoyed returning to campus for the annual scholarship dinners, where recipients and donors have a chance to meet. She reports, "Many students are surprised to learn that I and many others were also financial aid recipients. My hope is that they'll be inspired to give as well. To me, scholarship gifts are not so much about paying as they are about paying forward, investing in the future. The return on that investment—someone like me, sometime down the road—makes it the best investment you’ll ever make."

Hamilton adds that the average debt for a Skidmore education "seems eminently reasonable" compared to the far larger debt burden of some grads, especially those from the for-profit institutes. She says, "We know the intrinsic value of the Skidmore experience—from having close relationships with outstanding faculty (expert, dedicated professors, not just graduate students) to having seats available in courses so that students can graduate in their chosen major within four years. Supporting financial aid extends those life-changing educational opportunities to more students."

Jerome Mopsik is on board with giving back, too. The former Palamountain Scholar is now an organizer, along with wife Emily Carnevale Mopsik '07, for this year's Palamountain Scholarship polo benefit. He declares it "the best deal in town for a summer gala. The best food, the best company. It's just $125 per person. And it all goes to financial aid."

These and other scholarship supporters, from every era and area, tend to share a belief in liberal education as a personal, professional, and public good. Skidmore's codified "Goals for Student Learning and Development" set an expectation that graduates will, among many other things, acquire discipline-specific knowledge; understand social and cultural diversity; develop advanced learning skills, including the capacity to think critically, creatively, and independently; and hone their ability to analyze, integrate, and apply information and communicate the findings effectively. It’s a "daunting" list, as Glotzbach admitted at last year's commencement ceremony, but, he told the new grads, "the intellectual and ethical tool kit you have acquired through your Skidmore education provides you the best possible platform for success in a world marked above all by rapid, persistent, and unpredictable change." It's no coincidence that it's the same tool kit expressly sought, more and more urgently, by medical schools, law schools, and employers in practically every profession.

Education like that doesn't come cheap. What Skidmore does is necessarily cost-intensive—from its large faculty and personalized mentoring, to its laboratory, studio, athletics, and other resources, to its comprehensive First-Year Experience program, to its research, service, internship, travel, and other opportunities. But the more world crises that arise, the more Glotzbach sees Skidmore as an incubator of creative problem-solvers. That's why he and Bates and other Skidmore leaders not only defend the value of its ever more costly education, but also insist that it should be able to work its magic on a diverse community of the best and brightest students regardless of their finances.