2005 Summer Reading

The Burial at Thebes

Justice

by Prof. Michael Arnush, Classics

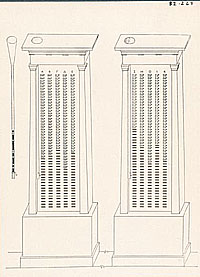

Reconstruction of a kleroterion

(courtesy Athenian Agora Excavations)

The Athenians were absolutely mad for the courtroom, and in the fifth century BCE the citizens practiced judicial procedures as a combination of high art and low farce. Citizens served as judges and juries, and anyone could bring a charge of any kind against another individual, which would then be played out in court. The state assigned no prosecutors or attorneys for the accused; instead, individual citizens brought cases to trial and the defendants defended themselves as best they could. The selection of a jury of peers was elaborate and constructed in such a way as to guarantee, as much as possible, a fair and impartial hearing. [The kleroterion (reconstructed here) functioned as a jury-selection machine; potential jurors' names, inscribed on lead tables, were inserted randomly into the columns, and a marble ball released through the tube on the left determined if a row of jurors would serve - a white marble for service, a black one for dismissal.] If Antigone’s case were to be brought to trial, Creon would prosecute and a male relative of Antigone’s would defend her. Of course, in the mythological world of the theater, and in this case set in a Thebes run by a monarch, no such trial would occur. Yet, the play has some of the trappings of the courtroom, for the dispute over the legality of Antigone’s actions occurs in an agon – a contest which emerges as a trial of sorts – between Creon and Antigone. The chorus stands in for an Athenian jury, and weighs in with its views on the limits of the actions of the two protagonists. So, while Antigone does not receive a proper legal hearing, the Athenian audience would surely interpret the play’s agon as reminiscent of the courtroom dramas that informed their lives.

Creon: So wrong-doers and the ones wronged fare the same?

Antigone: Polyneices was no common criminal.

Creon: He terrorized us. Eteocles stood by us.

Antigone: Religion dictates the burial of the dead.

Creon: Dictates the same for loyal and disloyal?

Antigone: Who knows what loyalty is in the underworld?

Creon: Even there, I'd know my enemy.

Antigone: And I would know my friend. Where I assist

With love, you set at odds.

Creon: Go then and love your fill in the underworld.

No woman will dictate the law to me. (pp. 33-34)

A bit later, the Chorus weighs in:

Chorus

O Zeus on high, beyond all human reach,

Nothing outwits you and nothing ever will.

You cannot be lulled by sleep or slowed by time.

O dazzle on Olympus, O power made light,

Now and forever your law is manifest:

No windfall or good fortune comes to mortals

That isn't paid for in the coin of pain. (pp. 39-40)

How would an Athenian jury, or in this case an Athenian audience, have adjudicated this dispute? We can never know for certain, but the words that Sophocles puts into the mouths of his characters hint at the appropriate moral and legal decision, which Creon clearly recognizes:

Creon

The hammer-blow of justice

Has caught me and brought me low.

I am under the wheels of the world.

Smashed to bits by a god.(p. 70)

The Athenians invoked and appealed to justice in all avenues of life, from dealing with extreme cases of homicide to the more mundane decisions about disputes over wills, property, taxation and contracts. Justice served to rectify disorder and chaos, to set right disharmony in the world, and although it was in the hands of men justice was also meted out by the gods.[1]

Antigone

By Justice, Justice dwelling deep

Among the gods of the dead. (p. 29)

Here, Antigone views justice personified as a god, assessing the behavior of humans in the afterlife. She expects that justice denied in the real world, the world of kings and subjects (and, in Athens, the world of the demos), would be apportioned only in death. The gods saw to the proper adjudication of disputes that men failed to realize, and so Antigone looks to a higher court for her case to attain final and fair resolution.

In our contemporary world in which some individuals think that justice can only occur through violence, where suicide bombers expect final resolution in the afterlife, we have confronted a type of justice unfamiliar to us before. Antigone does not perpetrate such violence against anyone other than herself, but she, too, expects that in the realm of the divine hereafter final and undiluted justice will attain.[2] Against an unmoving mortal court of opinion Antigone seeks redress not in the world of kings and subjects, but where justice dwells "deep / Among the gods of the dead."

[1] The Athenians reserved the courtroom for men only: citizens went before a jury

of peers, non-citizens sought justice in courts reserved for them, citizen-prosecutors

could subject slaves-as-witnesses to torture, and the Athenians prohibited women from

participating in legal proceedings. A woman seeking redress would have to appeal to

a man to defend her interests; barred usually from testifying, women depended on the

legal system of men only for the meting out of justice.

[2] Of course, Antigone's suicide precipitates the death of her beloved Haemon, the

suicide of Creon's wife Eurydice, and the destruction of Creon's world.