Using chemistry to solve archaeological mysteries

Leo Parra ’24 was asked to help try to solve two archaeological mysteries during his senior year at Skidmore.

Professor of Anthropology Heather Hurst ’97, who directs the San Bartolo-Xultun Regional Archaeological Project, turned to the chemistry major after returning from fieldwork in Guatemala with two samples that might shed light into the history of archaeological sites known for their remarkably well-preserved and stunning murals.

The first was a sample of pigment from a newly discovered mural that had been painted in an uncharacteristic style for the region and more closely resembled artwork from 3,000 kilometers (nearly 2,000 miles) away. Who created the mural?

The second sample involved an unknown, organic substance found in a burial context. What could it be?

With his academic background in chemistry, additional coursework with Hurst in archaeology, and extensive experience conducting research with faculty, Parra was uniquely qualified to help investigate.

“Leo is super enthusiastic, and I thought that this would be a great pairing between his chemistry interest and a chance to conduct hands-on work,” Hurst explained.

An interdisciplinary vision

The research that Hurst and Parra have been conducting with support from other Skidmore faculty is an example of the interdisciplinary vision that lies at the heart of Skidmore’s newly completed Billie Tisch Center for Integrated Sciences (BTCIS). The project fosters connections not only among the sciences, but also among the arts, humanities and social sciences. It further supports a broader liberal arts curriculum at Skidmore that emphasizes creativity, learning across disciplines, and making connections among an array of courses, ideas, and experiences.

“I think interdisciplinary work is extremely important, not just for young researchers, but also for learning's sake,” Parra said. “Of course, I enjoy doing my chemistry research, but I think there's a lot more value when we try and look at things through multiple different lenses.”

The recipient of a prestigious Skidmore’s Scholars in Science and Math Program merit scholarship Parra has been conducting chemistry research with Professor Kim Frederick since his first year at Skidmore. Frederick’s lab focuses on paper microfluidics, and Parra has worked on multiple projects with her, even contributing to a research study that will be published later this year. Parra has also conducted research with Associate Professor of Biology Jennifer Bonner and Associate Professor of Chemistry Kelly Sheppard. As a Skidmore student, Parra participated in a National Science Foundation-sponsored Research Experiences for Undergraduates program at the University of San Diego one summer.

The third and final phase of the Billie Tisch Center for Integrated Sciences will be ready for the fall semester.

But his interests aren’t limited to the natural sciences: Parra, who is from Arizona and identifies as Chicano, sought out courses at Skidmore that would deepen his understanding of his Mexican American heritage. He took archaeology courses with Hurst in the Anthropology Department and sought out a collaborative research project with her.

“I have taken three or four classes with Dr. Hurst. A year ago I told her I would love to do research with her,” Parra said.

Hurst’s work is distinct from the chemistry research Parra has been conducting: She specializes in archeological illustration, a method of creating drawings to record ancient artworks. The details Hurst finds while working on the drawings also allow her to uncover more information about the culture, society, history, and lives of the people who made the art.

Archaeological samples are one of a kind, a small piece of a larger artifact or artwork.

“These samples are quite difficult to acquire, and the Guatemalan government really entrusts us with them. We need to analyze them well and report back results,” Hurst explained. “I told Leo, ‘Explore how you can use the different instrumentation here at Skidmore.'”

The first sample Parra examined is pigment from one of the paintings in Guatemala. Archaeologists noted the painting closely matched a style from Teotihuacan in Central Mexico.

“The big anthropological question," Parra explained, “is if these people lived at the same time as the people who lived 3,000 kilometers away, did they go up to Central Mexico, look at the art, and replicate it? Or did the people from Central Mexico come down and paint for them?”

Using science to understand the past

Each culture in Mesoamerica has their own process and style, including how they make pigments. To carry out chemical analysis on pigment samples from the mural, Parra consulted with chemistry faculty, especially Frederick. He benefited from a range of resources in BTCIS, including its Skidmore McGraw Microscopy Imaging Center, which boasts an array of microscopes usually only found at major research institutions, and the Skidmore Analytical Interdisciplinary Laboratory, a collaborative suite featuring sophisticated instrumentation for chemical analysis.

“I used a scanning electron microscope (SEM) to take topological images of the surface of our samples. Along with that, I used a secondary electron scan to observe what elements are within a scanned region. These techniques have given us insight into what possible natural substances were used to make the mural,” he explained. “Raman spectroscopy also tells us about the potential molecules on the surface of our sample. This technique paired with the SEM offers insight into who may have been the artist to create the mural.”

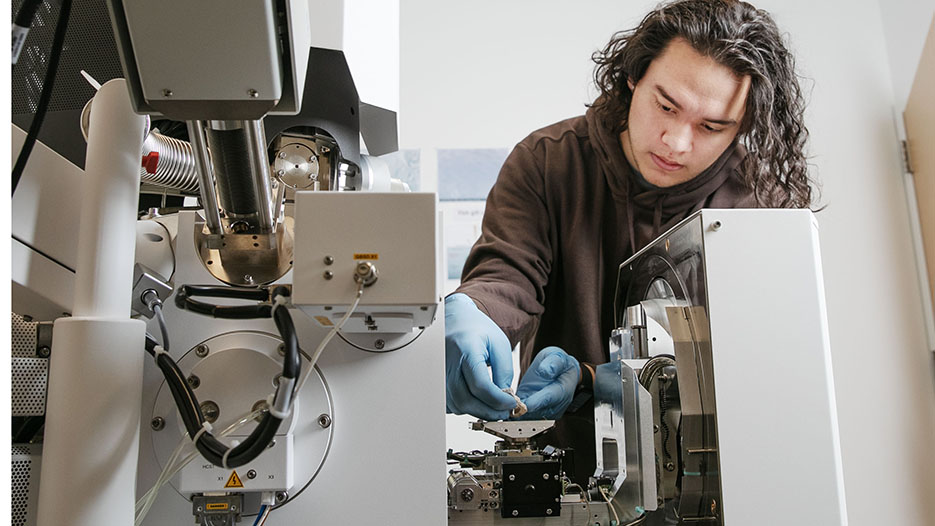

Leo Parra ’24 holds a sample that he is analyzing in the Billie Tisch Center for Integrated Sciences.

Preliminary analysis conducted by Parra indicated potential overlap with materials in what is now Central Mexico. But Parra cautioned that chemistry alone still couldn’t solve the mystery: Archaeologists would now need to explain how those materials and techniques made their way so far away.

The second sample Parra examined was an unknown material associated with a looted burial context from the site of Xultun. It is a collection of paper-like organic material sandwiched together.

Hurst had some hunches about the material – that it might be a burnt offering, for example.

“We know the general date, the building it was in, those general things. But in a given tomb, you might have many different materials,” Hurst explained.

Parra was able to determine the chemical makeup of the sample using the scanning electron microscope and identified residues on the surface but said more research was still needed.

“On the anthropological side, we still don't know what this potential offering is,” Parra said. “I can also say the same thing on the chemistry side: We still don’t know what this is.”

A longer research journey

Parra may not have solved that mystery, but it's all part of the scientific process and learning experience at Skidmore.

“Working in Dr. Frederick’s lab has made me more aware of the techniques scientists use. What kind of things should we be critiquing about our techniques and about our science that we then show to the public?” Parra says. “I have also grown to be more analytical: The experience of writing, doing the science, communicating my scientific work – that has absolutely been a highlight for me.”

And BTCIS — which brings all of Skidmore’s science programs and faculty under a single roof — has been central to that experience.

Having all of our sciences so close, and being able to walk from one professor to another — I think that's what really has made me enjoy the Billie Tisch Center for Integrated Sciences so much.”

After graduating in 2024, Parra’s undergraduate experience at Skidmore may have come to an end, but he is just beginning his research journey: He has been accepted into a doctoral program in biochemistry at the University of Arizona, where he plans to focus on virology. As he looks forward to working on new mysteries, he also looks back fondly at his Skidmore experience.

“Skidmore is a small liberal arts college, but we do big science here.”