2005 Summer Reading

The Burial at Thebes

Law

by Prof. Michael Arnush, Classics

For when the demos ("the people") have the vote, they have control of the state. -- Aristotle The Athenian Constitution 9.1

Athens was a city of law, and the democratic citizenry created law in the assembly and implemented it in the courtroom. Each place served as a crucible for the creation of a community bound by both divine and mortal laws, and unlike our contemporary society, ancient Athens did not always distinguish between the laws of the gods and the laws of men (and they were indeed the laws of citizen men only: women played no role in the legislative or judicial processes, and if prosecuted for an offense they had to have a male represent them in the courtroom; slaves were subjected to the laws established by their masters, who could beat them to death if they saw fit, and their only role in the courtroom was to serve as hostile witnesses tortured for information). Laws were fashioned with the sensibility that the gods were party to all legal actions, and were usually invoked both in the assembly and the courtroom as witnesses. The Athenians were just as likely to create a law regulating a sacrifice, or establishing a new cult for a god, as they were to erect trade barriers or negotiate treaties, and the Athenians would invoked the gods in the laws to testify to their proper implementation.

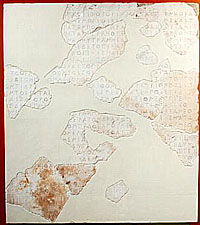

Athenian law regulating temple-worship,

ca. 485 BCE (Epigraphical Museum,

Athens)

A representative body of 500 men – the boule (pronounced “boo-LAY”) – served as the legislative organ of government, elected annually and charged with the responsibility of drafting legislation. Once it had drafted a new law, the boule brought it to the assembly of all male citizens – the ekklesia (“ek-klay-SEE-ah”) – who deliberated and then voted by raising their hands in support of the legislation; the majority always ruled. The surviving body of Athenian law grows annually, as archaeologists uncover stone inscriptions (often fragmentary, like the one here) in modern Athens which recorded the approved legislation and displayed them in public for all to consult. Laws were intended for public consumption, and so anyone who could read Greek could consult the laws erected throughout the city. This corpus of Athenian law indicates to us how invested the Athenians were in crafting legislation to regulate public and private life, and as they blurred the distinctions between the laws of the gods and the laws of men, so they also did not distinguish fully between the laws that governed public behavior and the laws that addressed the citizens’ private lives. This makes sense for a community in which citizenship was the sine qua non of life in Athens; to be a member of the polis was to be a polites – which we translate as “citizen” – and thus subject to the laws which addressed all aspects of life in the community.

Yet, though the Athenians did not always draw sharp distinctions between the public and private realms, or the divine and mortal, they did view divine law as paramount. Until the age of Socrates and Plato – the period of the late 5th and early 4th centuries after the Antigone – the Athenians believed that the laws of men did not, could not supersede the laws of the gods. Nonetheless, there were certainly moments when the Athenians thought that divine law was inexplicable – but that does not mean that they would challenge the gods’ will. The Athenians philosophized that mortal law would always yield to divine law, even if at times men could not fathom the gods’ intentions.

One crux of the Antigone resides in this conflict – does the law of the gods, which determines that a Greek slain in battle deserves a proper burial at the hands of his family, supercede the law of men – in this case, of King Creon of Thebes, who decided that the traitorous rebel Polyneices did not deserve funerary rites? Clearly the play indicates this issue as ambiguous, and Sophocles’ determination to display this conflict on the stage indicates that the Athenian citizenry wrestled with this dichotomy. Sophocles, deeply pious if we read his surviving works correctly, believed that in the end the gods had to be served, and so Antigone dies for this belief. Yet Sophocles and his audience lived in the world of Pericles, in which political decisions sometimes took precedence over righteous, moral and pious actions. By provoking an Athenian audience to consider this conflict, the playwright called into question those decisions by the state which could be construed as antithetical to the gods’ will.