2005 Summer Reading

The Burial at Thebes

Religion

by Prof. Leslie Mechem, Classics

Religion permeated every facet of Greek life. No notion of the separation of church and state existed. Both the polis and the individual worshipped gods who required prayers and sacrifices. If the community or the individual did not honor the gods appropriately, calamity could strike in the form of war, pestilence, or earthquake. All deities deserved recognition and attention, even though a variety of deities oversaw the many facets of life. A polis or citizen could never worship one deity exclusively. Therefore, although Athena, the preeminent city deity, served as the patron of Athens, the polis performed sacrifices to Zeus, Apollo, and others gods and goddesses as well. For instance, before entering battle, soldiers sang a hymn to Apollo to protect them against the enemy. Individuals made sacrifices and offered prayers to different gods depending on their stage of life or needs at a given time. For instance, an adolescent girl about to marry sacrificed her childhood toys, clothing and a lock of her hair to Artemis, the deity who oversaw the passage from childhood to adulthood. This sacrifice marked the beginning of a new phase in the girl’s life as wife and mother.

Sanctuaries, which included temples and altars, dotted the Greek landscape. Found in urban settings and the countryside, they offered sacred spaces where people performed the rituals which honored the gods. Individuals approached and engaged the gods primarily through sacrifice. Hymns and prayers accompanied all sacrifices, which included libations (liquid offerings to the gods) and burnt offerings of animals ritually killed over an altar.

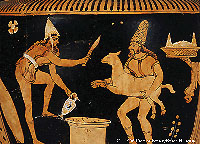

Apulian red-figure krater depicting the

sacrifice of a sheep (from a play?), 4th

c. BCE (University Museum, Univ. of

Pennsylvania)

As the priest cut the throat of the animal, its blood sprayed over the stone-built altar, a sign of the piety of the participants; then parts of the butchered animal burned on the altar so that the smoke reached the gods who enjoyed its fragrance. The priests and the community present cooked and consumed the rest of the meat, often the only time people regularly ate roasted animal flesh since it was a luxury. Individuals tended to offer smaller gifts to the gods, either honey cakes as a burnt offering, a piglet, or a wine libation. The distinction between sacred and secular space blurred in such areas as the agora, the marketplace in a Greek city. Technically, the agora constituted sacred space and boundary markers indicated when one entered it; however, the agora did include shopping facilities, civic buildings, and racecourses. Clearly, the use of the agora as a blend of the sacred and profane indicated that the gods oversaw every facet of Greek life and were never far from the consciousness of the people.

We see the prevalence of the gods in the Greek mind reflected in The Burial at Thebes. In the first lines of the play Antigone says, “There’s nothing, sister, nothing / Zeus hasn’t put us through” (p. 5), indicating her understanding that life’s trials and tribulations ultimately came from the gods. When the Guard reports that someone has buried Polyneices, the Chorus states, “I cannot help but think / The gods have had a hand in this somewhere” (p. 21).Clearly, the Greeks attributed to the gods much if not all that happened in the human realm.